Why Write about Trauma? By Lisa Braver Moss

I have a nice life. I’m blessed with wonderful work, I’m in good health, I’m comfortable, I’ve been married for 36 years, and I have two delightful grown sons. Besides, I’m a positive person. I don’t like to focus on misery for its own sake.

I have a nice life. I’m blessed with wonderful work, I’m in good health, I’m comfortable, I’ve been married for 36 years, and I have two delightful grown sons. Besides, I’m a positive person. I don’t like to focus on misery for its own sake.

So why would I want to write about my violent, traumatic childhood? Why not leave well enough alone?

There’s plenty of social pressure to avoid such a topic. To write about it is to dredge up the past. I could be accused of being negative, self-serving, not nice. But all this assumes I have a choice in the matter when really, my writing topics seem to choose me. I write because I can’t stand not to take action when a topic calls to me.

Besides, I love taking disorder and making something cohesive out of it. I love digging into thorny topics and finding a way to make them understandable. The process, while frustrating at times, is exhilarating when it’s going well.

When it comes to autobiographical writing such as my novel Shrug (She Writes Press, August 2019) the stakes are high: I feel very exposed, but also value the opportunity to feel seen, understood. Here are the reasons I kept going until I had a book.

A way out of shame and isolation. Like many childhood trauma survivors, I sometimes find myself feeling ashamed of how I grew up: ashamed that my father couldn’t control his fists, ashamed that my mother abandoned the family. I know that’s illogical; my circumstances weren’t my fault. But then, shame isn’t logical.

I like to think that in writing about trauma and sharing my work with others, I’m helping to counter the sense of isolation that accompanies shame: I feel this way, so if you feel this way, too, you’re not alone, and neither am I.

Self-compassion. In my earliest drafts of Shrug, I found it challenging to create a sympathetic main character. That’s how hard it was for me to stand back and view her with love and compassion. It turned out that the relentless self-criticism habit I’d developed as a young child was bleeding through into my work. As I honed draft after draft, I found ways to fix the problem in the manuscript. The more lovable I made the main character, the more compassion I felt for her and, by extension, for myself.

Control. As a child, I wanted control over my circumstances so badly that I construed our household chaos as something having to do with me. I didn’t exactly think the violence was my fault; more that it was my job to fix it. My brain was so pained by my lack of control that it tricked me into thinking I did have control and that it was just a matter of my not putting in enough effort or my not understanding something. Somehow, my failure was more palatable than the idea that there was nothing I could do. It was certainly more palatable than the idea that my parents weren’t looking out for me.

As a writer, I’m in charge of all the details, the spin, and the end result. I’m free to go back and rework the material as many times as required to get it precisely right. In the process, I’m making order out of the uncontrollable chaos I experienced as a kid. I get to feel I’m finally in the driver’s seat.

It wasn’t personal. One of the most difficult things about being mistreated as a child is that the abuse feels personal. As a child, I metabolized my mistreatment as something resulting from my elemental badness. In the process of finding the precise words to describe my main character’s situation, I’ve gotten more and more freedom from the idea that the abuse had anything to do with my character. The details make it clear that the mistreatment revealed something about the perpetrators rather than about me.

It really was that bad. I blend in well with people, and when I refer to having had a difficult childhood, I’m often told the person had no idea. Sometimes people look at me with cheery skepticism: It can’t have been that bad. You turned out so well! It’s as if I’m being told that I’ve successfully “gotten over” all that. People are also impressed that I chose to be an achiever rather than turning to drugs, alcohol, etc.

While I appreciate these compliments and am grateful to be able to give the impression of health and well-being, I don’t want to be talked out of my reality. There is no “getting over” significant childhood trauma. Writing about it makes me feel I’ve been true to what actually happened.

Making it finite. In writing about my trauma, I’m objectifying it, externalizing it, letting it be as bad as it was—and therefore limiting it. This is an antidote to my sense that the trauma was infinite, that I’ve been hurt too deeply ever to heal.

Beauty from ugliness. Writing about my childhood feels redemptive to me, an opportunity to make something beautiful out of something ugly. Even if some readers wince because of the painful content, or skip my writing entirely, I find it fulfilling to have created a coherent narrative out of chaotic, difficult stuff. Paradoxically, the exercise requires both distance from the material, and special attention to its particulars. I find the task so absorbing and complex that it puts me in a different relationship with the trauma. That in itself provides a kind of relief.

While it’s been cathartic to write about my trauma, I hope the result offers more than my own personal catharsis. I hope my writing helps others feel less isolated, more self-compassionate, less ashamed and more “seen.”

—

Lisa Braver Moss is a writer specializing in family issues, health, Judaism and humor. Her essays have appeared in the Huffington Post, Tikkun, Parents, Lilith, and many other publications. She is the author of the novel The Measure of His Grief (Notim Press, 2010). Her second novel, Shrug, is out now, by She Writes Press.

Lisa’s nonfiction book credits include Celebrating Family: Our Lifelong Bonds with Parents and Siblings (Wildcat Canyon Press, 1999) and, as co-author, The Mother’s Companion: A Comforting Guide to the Early Years of Motherhood (Council Oak Books, 2001). She is co-author, with Rebecca Wald, of Celebrating Brit Shalom (Notim Press, 2015), the first-ever book of ceremonies and music for Jewish families seeking alternatives to circumcision.

Born in Berkeley, California, Lisa still lives in the area with her husband, with whom she has two grown sons.

Find out more about her on her website https://www.lisabravermoss.com/

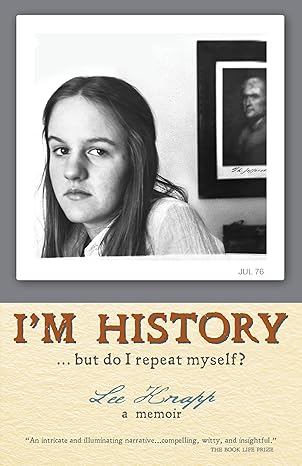

SHRUG

It’s Berkeley in the 1960s, and all Martha Goldenthal wants is to do well at Berkeley High and plan for college. But her home life is a cauldron of kooky ideas, impossible demands, and explosive physical violence. Her father, Jules, is an iconoclast who hates academia and can’t control his fists.

It’s Berkeley in the 1960s, and all Martha Goldenthal wants is to do well at Berkeley High and plan for college. But her home life is a cauldron of kooky ideas, impossible demands, and explosive physical violence. Her father, Jules, is an iconoclast who hates academia and can’t control his fists.Martha perseveres with the help of her best friend, who offers laughter, advice about boys, and hospitality. But when Willa and Jules divorce and Jules loses his store and livelihood, Willa goes entirely off the rails. A heartless boarding school placement, eviction from the family home, and an unlikely custody case wind up putting Martha and Drew in Jules’s care. Can Martha stand up to her father to do the one thing she knows she must—go to college?

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

You wrote eloquently about all the reasons to write. Stories organize meaning, and re-telling is a lifelong search for meaning.

Beautiful work, Lisa.