Pommes Frites

Pommes Frites

In the spring just before my daughter turned ten, my husband’s parents invited us to share an apartment they had rented for a week in Paris. Michael didn’t have the vacation time, so I decided to bring our daughter, Sophie, as a special 10th birthday trip. It was my chance to show her why the City of Light had cast its spell on me as a college student during my junior year abroad.

“You two are going to have so much fun!” my husband said at breakfast a few days before we left.

“You know, Sophie,” I added, “every little bistro in Paris is candle-lit and has skinny French fries. Only there they just call them fries.” It was our little joke. We repeated it often with French windows, French braids, and French bread.

When we arrived at the apartment on Île Saint-Louis, I was thrilled that our French windows (just windows in France) looked directly onto the Seine, and that we were able to walk easily to many of our destinations. As we strolled down the cobbled street on our first day past creperies, olive oil stores, and dazzling patisseries, the possibilities that stretched out before us was almost more than I could bear. My chest felt full and buoyant with anticipation. I had never played the tourist when I lived there as a student. Now I would finally have a chance to be a tourist with my daughter—to climb the Eiffel Tower and Sacré Coeur, ride the Bateaux Mouches, and revisit all my favorite haunts.

So, for the next six days we wandered hand in hand by monuments and churches and through towers and museums, while I pointed and moaned faintly with nostalgia.

It wasn’t easy to separate the city from the life-changing romance I had had with Luc, the 29-year-old married French lawyer I met while singing in the chorus of the Orchestra of Paris. On the steps of the Palais de Justice, I took Sophie’s photo, smiling at her tiny figure with stubby ponytail, short skirt, and cross-body purse, the immense chiseled letters, LIBERTÉ, EGALITÉ, FRATERNITÉ, overhead. She looked so small. What did I look like, I wondered, meeting Luc on these same stairs in 1977?

It wasn’t easy to separate the city from the life-changing romance I had had with Luc, the 29-year-old married French lawyer I met while singing in the chorus of the Orchestra of Paris. On the steps of the Palais de Justice, I took Sophie’s photo, smiling at her tiny figure with stubby ponytail, short skirt, and cross-body purse, the immense chiseled letters, LIBERTÉ, EGALITÉ, FRATERNITÉ, overhead. She looked so small. What did I look like, I wondered, meeting Luc on these same stairs in 1977?

“Where are we going?” Sophie would ask me every few minutes as we walked around the city.

“I don’t know yet, honey,” I said.

In Paris, I never knew. As a student, I used to walk for hours, sometimes entire days, until my calves ached, and my feet pulsed with pain. The intrinsic beauty of the bridges and cobbled squares created a bottomless pit of yearning that made it impossible to choose in which direction to wander. And it proved a heady mix for a small-town Maine girl like me who had never lived in any big city before. At first I floated through the streets in a blurry state of disbelief, light-headed from bus fumes that mingled with the intoxicating aroma of warm croissants wafting from the boulangeries. It soon felt as if all the pieces of the cosmic puzzle were fitting together. I was meant to live here.

“But what are we gonna do now?” Sophie tried again, skipping over cracks, hopping on one foot, and yanking on my hand when I least expected it.

“Well,” I began, beads of sweat rising on my forehead, “we could either go to the Museé d’Orsay first to see the impressionists, and then over to the Opera to see the Chagall ceiling, or we could save the museum for a rainy day, and just walk through the Tuileries to the big new Ferris wheel, and then we could walk up the Champs Elysées to see the Arc de Triumph. But . . . I don’t know, it’s so hot out, maybe we should just see a movie to rest and cool off. Do you think you are up for more walking? I could show you where I took my classes near Montparnasse, or would a shady park be more fun right now? There are so many beautiful ones . . . What I really want to do is to show you my old neighborhood where I lived in my little chambre de bonne on rue Bonaparte and we could walk around and look in old kiosks along the river . . .”

“Well,” I began, beads of sweat rising on my forehead, “we could either go to the Museé d’Orsay first to see the impressionists, and then over to the Opera to see the Chagall ceiling, or we could save the museum for a rainy day, and just walk through the Tuileries to the big new Ferris wheel, and then we could walk up the Champs Elysées to see the Arc de Triumph. But . . . I don’t know, it’s so hot out, maybe we should just see a movie to rest and cool off. Do you think you are up for more walking? I could show you where I took my classes near Montparnasse, or would a shady park be more fun right now? There are so many beautiful ones . . . What I really want to do is to show you my old neighborhood where I lived in my little chambre de bonne on rue Bonaparte and we could walk around and look in old kiosks along the river . . .”

“All the neighborhoods look the same to me,” she said.

I deflated, the air leaving my body like a punctured balloon.

My maid’s room in 1977 on rue Bonaparte was sparse and threadbare, but I would fill empty Chianti bottles with candles and flowers, and tape art prints to the walls. Through its tiny square window I could see the rooftops of Paris, and when it rained, the sound on the zinc roof overhead was mesmerizing and poetic. After saying goodnight to Luc, I would climb to the sixth floor and collapse on my low bed beneath the eaves to read Madame Bovary and listen to my radio. I felt safe and happy and didn’t care about the dozens of writers who had described the magic of this city. It had become my Paris. But how could Sophie possibly care?

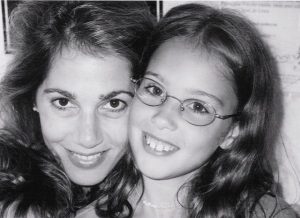

My daughter was bright, musical, and my closest confidante since her earliest years. At four, she thoughtfully considered her future and stated, “I want to be a musician like Mommy, but I want to be smart like Daddy,” and consoled me when she looked at the low horizontal C-section scar I had from her new baby brother: “It doesn’t matter, mommy; anyway, you needed a decoration.” Would she even remember this trip in five years? When do memories start to count?

I never missed adult company when we were together, but it was taxing to be responsible for the success of the trip. After walking all day long, we would collapse on our beds in the apartment on Quai d’Anjou at seven in the evening to rest. By the time we ventured back out at nine o’clock for dinner, we were just too hungry and tired to leave our quartier on Îe Saint-Louis. The skinny French Fries I had promised Sophie were nowhere to be found at these upscale, candle-lit bistros. We would study the menu from outside, and I would search anxiously for something I thought she would eat.

We poked our head into one: “Do you have pommes frites?” I asked in French, slightly apologetically, indicating my daughter by my side.

“Mais non, pommes gratinées,” the waiter replied with condescension, implying that only lowly brasseries served them. The search for French fries was starting to take on symbolic importance. With every failed attempt to find them, my stomach tensed uncomfortably. Sophie and I entered and sat down anyway, as she cozied up with her drawing pad. While I sipped my goblet of red wine, Sophie lost herself in drawing ladies with poufy dresses, tiny waists, and bouffant hairdos. I heard her whispering French words that she was starting to recognize: du pain, du beurre, de l’eau s’il vous plait, poulet roti. Maybe there was hope after all.

“It’s smart that they have pigeon on the menu,” Sophie announced, never looking up from her drawing pad, “‘cause there are so many in Paris, they’ll never run out.”

One afternoon we ventured over to the Garnier Opera House, where we sat on the marble staircase and posed for photos next to the immense statues of the composers Gluck and Handel. We gasped together at the breathtaking dome ceiling by Chagall inside. As we sat at Café de la Paix afterwards, facing the grandiose entrance of the Opera across the street, Sophie ordered a bowl of three sorbets – cassis, citron, and framboise. I was gazing at the words Académie de la Musique, just visible from under the awning of our café, and remembering the time I sat right near Arthur Rubinstein who listened with closed eyes to the arias of The Magic Flute, when Sophie announced, “I think I found the perfect combination of these sorbets to eat together: a little bit of this one, a lot of this one and a medium amount of this one. No, no, a medium amount of this one, a little bit of that one and a lot of this one,” as she found endless combinations of how to eat this dessert, gliding her spoon over the perfect balls of deep purple, fuscia, and yellow. Perhaps she had found her own way to understand Paris.

The day before our flight home, I decided to bring my daughter to Closerie des Lilas, my favorite old-world café from those rose-tinted days of my year abroad. For three consecutive nights I had ended up in the amber-toned piano bar with Luc after singing Beethoven’s Ninth with the Orchestra of Paris, and we had sat at a corner mahogany banquette, staring into our wine, drenched with emotion and music.

“Someone’s smoking!” Sophie exclaimed when we walked into the café. “Why do French people smoke so much if they know it’s bad for them?”

We found a table outside on the terrace instead to avoid the smoke.

“I can’t believe they let dogs into restaurants here!” my daughter beamed. “Mom, will you just order for me? Do you still have my book in your bag?”

I dug through our tote, moving aside our map of Paris, her lightweight sweater, a travel umbrella, a small bag of museum postcards, and a drawing pad. I handed Sophie her book, The Golden Compass, by Phillip Pullman. Sophie began reading, entering happily into her private world. I tried to fight the feeling of estrangement and the small lump forming in my throat. I had wanted to relive the intimate ambiance of the piano bar inside, just as I remembered it.

On our final morning, we awoke to a gray, drizzly, Parisian sky, but took one last walk along the quais with Notre Dame never very far from view. The deep green hues of the trees hung low over the river, and Paris in the rain looked poetic and sad, as only it can. I was still reliving my memories.

“Look Sophie, this is Place Dauphine,” I said.

“Looks like Boston,” my daughter answered, still lurching in unexpected directions as she hopped over cracks in the sidewalk. “Next time can we do Paris countryside?”

It was no use. Though I tried to transfer to Sophie the magic I had experienced living in Paris at twenty, in the end Sophie was a decade too young to be captivated by its radiance. It was my past, my magic. Hers was out there somewhere, probably not even in France. Though we had lots of fun together, to Sophie, Paris was just like any other big, dirty city.

And perhaps it was even a couple decades too late for me. As a taxi drove us to the airport, I turned around in my seat and watched the quaint streets and bridges recede quickly into the distance, as if they no longer warranted a closer look. As if I were finished with Paris. I felt let down in a way I couldn’t explain. I’m never coming back, I heard myself think. A door had shut. Open it now and I would find no enchanted garden.

“Sophie,” I tried one last time. “Can you see yourself coming to Paris on a school year abroad program, living in a little room somewhere, and and taking classes and piano lessons?”

“I dunno, maybe,” she answered. “Mom, do you still have that green apple in your bag? Who was Granny Smith, anyway?”

—

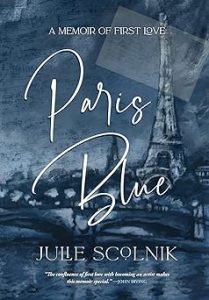

JULIE SCOLNIK is a concert flutist and the founding artistic director of Mistral Music, a chamber music series which since 1997 has been known for its virtuosic artists, imaginative programming, and the personal rapport she establishes with her audiences. In 2021 Scolnik released her debut memoir, Paris Blue, a true fairytale memoir (with a dark underbelly) set against a backdrop of classic music and Paris in the late seventies, about the grip of first love. http://www.JulieScolnik.com

All photos by Julie Scolnik.

PARIS BLUE: A MEMOIR OF FIRST LOVE

“Not every true story is like a good novel, but this one is. Not every memoir of first love has a satisfying ending, but this one does. The confluence of first love with becoming an artist makes this memoir special.” —John Irving

PARIS, 1976: Twenty-year-old American student Julie Scolnik had just arrived in the City of Light to study the flute when, from across a sea of faces in the chorus of the Orchestre de Paris, she is drawn to Luc, a striking (married) French lawyer in the bass section. This moving tale of an ebullient young American and a reserved Frenchman will transport readers to the cafés, streets, and concert halls of Paris in the late seventies, and, spanning three decades, evolves from deep romance to sudden heartbreak, and finally to a lifelong quest for answers to release hidden, immutable grief.

PARIS, 1976: Twenty-year-old American student Julie Scolnik had just arrived in the City of Light to study the flute when, from across a sea of faces in the chorus of the Orchestre de Paris, she is drawn to Luc, a striking (married) French lawyer in the bass section. This moving tale of an ebullient young American and a reserved Frenchman will transport readers to the cafés, streets, and concert halls of Paris in the late seventies, and, spanning three decades, evolves from deep romance to sudden heartbreak, and finally to a lifelong quest for answers to release hidden, immutable grief.

Against a magical backdrop of Paris and classical music, Paris Blue is a true fairy-tale memoir (with a dark underbelly) about the tenacious grip of first love.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing