Lost and Found in a Hearing World: Finding My Voice in My Writing

Lost and Found in a Hearing World: Finding My Voice in My Writing

By Claudia Marseille

When I was ten I bombed my oral report on Abraham Lincoln in front of the school auditorium packed with expectant parents, teachers and invited guests. I stood frozen in front of the room. Even though I understood what I wanted to say, there was a gap between what I “knew” in my head, and what I was able to express. This humiliation was so great that I successfully managed to avoid public speaking for decades.

By age four I’d hardly uttered a word. Most children speak short phrases by age two-three years, but my parents, refugees from Nazi Germany, were too distracted with adjusting to life in America and were in denial that something was amiss. Finally, my nursery schoolteacher insisted my parents take me to an audiologist, and I was diagnosed with a severe, bordering on profound, hearing loss. My loss was probably due to anti-nausea medication my mother was given when she was pregnant with me.

My first hearing aid at age four was a primitive, clunky analog one, as big as a deck of cards, that clipped onto my T-shirt and was fastened by a long cord to a customized mold in my ear. This was in the mid-1950’s, long before the sophisticated digital hearing aids of today. I then began the long, arduous process of learning to hear, lip read and speak along with ten years of speech therapy. Sadly, it is likely that my hearing had deteriorated significantly since birth as I had lost several years without hearing anything at all. Ear nerves atrophy if they aren’t stimulated with sound.

My parents chose to mainstream me in public schools, and while I was largely successful at school, I paid a significant price, many times facing social isolation, and loneliness. I had trouble understanding what was said in group situations in the school cafeteria, in restaurants, at parties, on the TV, and the radio. In these situations, I simply couldn’t understand what people were saying. In addition, until recently, I’d great difficulty understanding what was said on the phone.

This made it virtually impossible for me to socialize as a teenager with my friends who talked for hours on the phone every evening. Responding to a proposed date by telephone was challenging and embarrassing as I didn’t want to ask my mother to take over the phone call. Finally, I couldn’t follow the TV shows or understand the lyrics of the popular music on the radio that mesmerized my peers. Too often there was a voice over narration making it impossible to lipread. All this kept me from connecting with the mainstream culture of the time and was a source of great frustration and pain.

Additionally, I had a complicated relationship with my German refugee parents, a disturbed psychoanalyst father, and Jewish mother, survivor of the Holocaust. They were too pre-occupied with troubles of their own to recognize my struggles and fully advocate for me and so I had to navigate my way largely on my own through the substantial challenges of being mainstreamed in public schools.

During my childhood, although I did eventually learn to speak, I often simply wasn’t able to access the words I wanted to express myself. I was close to my brother Elliot who was two years younger than me, and very articulate. As siblings do, we got into periodic fights, and he was able to run circles around me with sophisticated arguments. I knew what I wanted to reply to him but I couldn’t find the words to argue back. Maybe because I learned to speak so late, and my vocabulary was behind that of my peers, words weren’t readily available to me. There was a gap between my knowing of what I wanted to say and being able to articulate my feelings. Same with my mother; periodically she would get angry at me about something I’d done or said and I wanted to defend myself. But again, I couldn’t find the words to express myself. This was a great source of frustration for me and left me feeling impotent.

Later in middle and high school, I experienced similar difficulties during class discussions. My teachers and most other students didn’t know about my hearing loss; I was too ashamed and shy to tell everyone. I suffered numerous painful and embarrassing situations when I finally would speak up, only to find the other students sniggering and the teacher staring non-plussed at me. Clearly, by the time I responded to what I thought the topic was, the discussion had moved on to something else. I was unable to track what others had said and where the conversation was going. After a few of these painful incidences, I decided it was easier simply not to speak up.

This was long before children were taught to advocate for themselves, and certainly before the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 which required accommodations in the classrooms, such as closed captioning of films, optimal seating arrangements, and projection of the teacher’s notes onto a screen at the front of the room. Nowadays, often teachers are fitted with FM assisted listening devices which transmits their voice clearly into their students’ hearing aids.

Likewise, I suffered similarly in social situations in the school cafeteria. Hearing and discriminating speech above background noise is always challenging for those with a hearing loss. This was particularly difficult when I was younger and using analog hearing aids that couldn’t yet be programmed for a particular frequency profile as today’s digital aids can. I had trouble hearing and following the freewheeling discussions of noisy teenagers all around me. As I couldn’t insert myself into any of the conversations, I withdrew into myself; silent and invisible, stuffing my pain as much as possible. I wasn’t able to speak the truth about my experience of living with a severe hearing loss.

I’ve always relied on one other special person who would act as a bridge between me and the larger world. The first such person was my brother. He would take care to look directly at me and articulate clearly and explain what was happening in the car, what the rules of the games were that we played with the neighborhood kids, and what was going on at family gatherings around the dining room table. Later it would be a best friend, boyfriends, my first husband and now, for many years, my current husband. They acted as my ears, explaining social dynamics, and also repeating what had just been said by someone else. And very importantly, they often made phone calls on my behalf. In so many instances, they became my voice.

However, for years now, I’ve been able to speak fluently, and my friends know me as articulate. The advent of modern technology such as Bluetooth connectivity, closed-captioning, sophisticated digital hearing aids, and assistive listening devices have made a tremendous difference in my ability to participate more fully in life. Also, with maturity, supportive family and friends, therapy and a steady meditation practice, I’ve largely found peace with my past and my hearing loss.

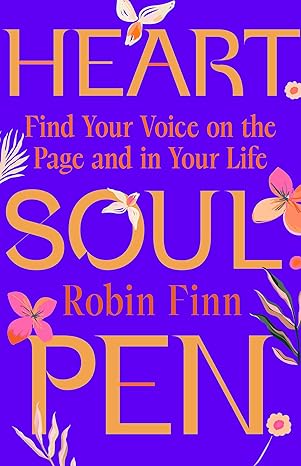

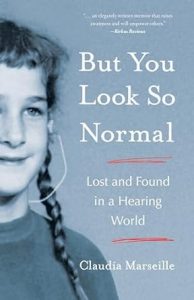

But very importantly, the process of writing my memoir, “But You Look So Normal”, has been healing. With the written word I’ve finally been able to express the truth of my experience of living with a severe hearing loss that I’ve found so difficult and painful to verbalize. Now, as I approach the prospect of speaking in public about my memoir I see this as an opportunity to release the young child in me that still believes she can’t access her voice.

I’m ready to embrace the challenge of bringing my story to life through the spoken word. I hope my narrative is a testament to the power and importance of expressing one’s experience to the benefit of all of us who struggle to find our voice and truth. Through my story, I hope to highlight the capacity of the human spirit to overcome significant difficulties, to create empathy and compassion and to help promote understanding for those of us who face differences in abilities.

—

BUT YOU LOOK SO NORMAL: LOST AND FOUND IN THE HEARING WORLD

feaBy age four, Claudia Marseille had hardly uttered a word. When her parents finally had her hearing tested and learned she had a severe hearing loss, they chose to mainstream her, hoping this would offer her the most “normal” childhood possible. With the help of a primitive hearing aid, Claudia worked hard to learn to hear, lipread, and speak even as she tried to hide her disability in order to fit in. As a result, she was often misunderstood, lonely, and isolated—fitting into neither the hearing world nor the Deaf culture.

feaBy age four, Claudia Marseille had hardly uttered a word. When her parents finally had her hearing tested and learned she had a severe hearing loss, they chose to mainstream her, hoping this would offer her the most “normal” childhood possible. With the help of a primitive hearing aid, Claudia worked hard to learn to hear, lipread, and speak even as she tried to hide her disability in order to fit in. As a result, she was often misunderstood, lonely, and isolated—fitting into neither the hearing world nor the Deaf culture.

This memoir explores Claudia’s relationships with her German refugee parents—a disturbed, psychoanalyst father obsessed over various harebrained projects and moneymaking schemes and a Jewish mother who had survived the Holocaust in Munich—and with her own identity. Claudia shares how she emerged from loneliness and social isolation, explored her Jewish identity, struggled to find a career compatible with hearing loss, and eventually opened herself to a life of creativity and love.

But You Look So Normal is the inspiring story of a life affected but not defined by an invisible disability. It is a journey through family, loss, shame, identity, love, and healing as Claudia finally, joyfully, finds her place in the world.

BUY HERE

At age four, Claudia Marseille was diagnosed with a severe hearing loss. With determination and the help of powerful hearing aids, she learned to hear, speak and lipread. She was mainstreamed in public schools in Berkeley, CA. After earning master’s degrees in archaeology and in public policy, and finally an MFA, she developed a career in photography and painting, a profession compatible with a hearing loss. Claudia ran a fine art portrait photography studio for fifteen years before becoming a full-time painter. Her paintings are represented by the Seager Gray gallery in Mill Valley, CA, and can be seen at www.claudiamarseille.com.

She has played classical piano much of her life; in her free time she loves to read, watch movies, travel, spend time with friends, and attend concerts and art exhibits. She and her husband live in Oakland and have one grown daughter.

Find out more about her memoir at www.claudiamarseilleauthor.com.

Facebook: www.facebook.com/Claudiamarseilleauthor (author page)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/claudia.marseille/ (personal page)

Instagram: www.instagram.com/claudiamarseille

Linked In: www.linkedin.com/in/claudia-maseille-49620384

Category: On Writing