Song of the Sea Maid and Prehistoric Women

My second novel, SONG OF THE SEA MAID, tells the tale of Dawnay Price, an orphaned girl in London in the 1730s who stumbles upon the good fortune to find a benefactor and be educated. It is clear from her earliest days – lying on a hard bed and counting windowpanes, multiplying them in her head – that she has a mathematical and scientific bent. She yearns to become a scientist, or in the parlance of the day, a natural philosopher.

My second novel, SONG OF THE SEA MAID, tells the tale of Dawnay Price, an orphaned girl in London in the 1730s who stumbles upon the good fortune to find a benefactor and be educated. It is clear from her earliest days – lying on a hard bed and counting windowpanes, multiplying them in her head – that she has a mathematical and scientific bent. She yearns to become a scientist, or in the parlance of the day, a natural philosopher.

In her later travels to study, one of her interests becomes the idea of early humans. The image of people living in caves, a primitive human yet with the same brain capacity as you or me, is a familiar one to us these days. But in Dawnay’s time this was almost unheard of. Religion and reading the Bible led most of Dawnay’s contemporaries to believe that humans were created in God’s image and had stayed the same throughout history.

But there were some folk in Dawnay’s era who were questioning the orthodoxy. Bones were being found – giant bones of animals no longer extant on the earth – and thinkers were proposing a range of ideas of how they got there, long before the term ‘dinosaur’ was coined in the C19th. Fossils had been dug out from rocks for a long time and even Leonardo da Vinci tried to figure out how they got there.

And artefacts in dwellings from the earliest days of human existence were common finds in countries as wide as Africa, to Australia, to France, Spain and England, where ancient Avebury standing stones were knocked down to build walls and prehistoric tools were mistaken for thunderbolts, formed in storm clouds and rained down upon the land.

From that time to this, religion and science have not always been easy bedfellows, to say the least. As science proceeded, religion had some hard questions asked of it, and pioneers such as Charles Darwin in the C19th had to run the gauntlet of criticism from those who felt scientific theories were dangerously close to a form of blasphemy.

From that time to this, religion and science have not always been easy bedfellows, to say the least. As science proceeded, religion had some hard questions asked of it, and pioneers such as Charles Darwin in the C19th had to run the gauntlet of criticism from those who felt scientific theories were dangerously close to a form of blasphemy.

As a woman of lowly birth living 100 years before Darwin published his theories, my character Dawnay had much greater obstacles to overcome if she were to become a scientist at all, let alone have her theories heard or accepted. If only she had been born in the modern era, in the C20th, for example, wouldn’t her ideas have fallen on fertile ground instead? Well, that’s not so sure either…

As part of my research for this novel, I read an excellent study edited by Lori D. Hagar called ‘Women in Human Evolution’. The book looked at paleoanthropology – the study of human evolution – and took as its focus the women who have worked within this field yet also the view of women in the human past. It questions the idea central to many classic C20th studies that it was the human male that drove human evolution.

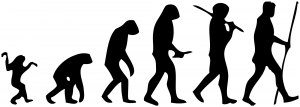

If you Google ‘human evolution’ images, many of the diagrams of apes transforming over time into humans will use males as their model – not all of them, but most of them. And the final image in the line is that of a modern male human, standing boldly upright in all his glory – Man.

So, what about Woman? What on earth was she doing, while Man was driving forward evolution by hunting animals and running on two legs across the African savannah? I don’t claim to know much about paleoanthropology – I’m a novelist and certainly no scientist – but this question, of what women were doing in early history does fascinate me, as it does my heroine Dawnay Price.

So, what about Woman? What on earth was she doing, while Man was driving forward evolution by hunting animals and running on two legs across the African savannah? I don’t claim to know much about paleoanthropology – I’m a novelist and certainly no scientist – but this question, of what women were doing in early history does fascinate me, as it does my heroine Dawnay Price.

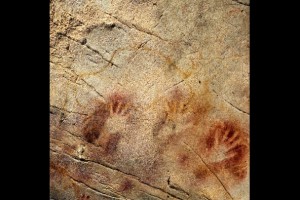

A good example of early history that seems dominated by males in our imagination is cave painting. When I was researching for SONG OF THE SEA MAID, I carried out a small (and highly unscientific) survey of friends and family, with a range of questions about how they imagine cave paintings to have been produced.

Almost every single respondent answered that they pictured men painting the walls of caves. Again, if you search online for modern artistic portrayals of humans painting cave walls, most of the images you’ll find are those of men daubing the walls – and what do we call them? Cavemen. But, on what evidence is this based?

Almost every single respondent answered that they pictured men painting the walls of caves. Again, if you search online for modern artistic portrayals of humans painting cave walls, most of the images you’ll find are those of men daubing the walls – and what do we call them? Cavemen. But, on what evidence is this based?

Well, it turns out, not a huge amount. In fact, once you start to look into it, you’ll find that some of the latest research suggests the possibility that many of the handprints surrounding some of the world’s most famous cave art sites are female hands. We don’t know who painted the animals, but we do know that women were there planting their identity in the form of hand-marks all the way round the main images.

And if we follow the idea that men did the hunting (which is not necessarily true of all cultures), then who would have done the butchery? If it were women who prepared and cooked the animals, wouldn’t it make sense that women would have had the most intimate knowledge of animal physiology and thereby be the best judge of form when coming to paint such animals on the walls of their caves?

These thorny questions and more tax my mind, and that of Dawnay Price. I’m getting a bit tired of hearing about Early Man and Cavemen. That’s why I don’t tend to use these terms myself. You might say I’m being fussy, that names for things don’t matter, or even that it makes sense that men drove things forward, doesn’t it?

I’m not saying it was women who drove it either. I’m just looking for a bit of parity, some sense that early people were equally engaged in evolution, girl or boy, man or woman. Dawnay was born a female into poverty almost 300 years ago, and had these obstacles to overcome in order to fulfil her ambitions. But we’ve come so far since then. Haven’t we?

—

Rebecca Mascull is the author of two novels published by Hodder and Stoughton. THE VISITORS is the story of Adeliza Golding, a deaf-blind girl living on her father’s hop farm in Victorian Kent; it was nominated for the Edinburgh Festival First Book Award. SONG OF THE SEA MAID follows Dawnay Price, an eighteenth century orphan who becomes a scientist and makes a remarkable discovery. Rebecca lives by the sea in the east of England with her partner Simon, their daughter Poppy and cat Tink. She has worked in education and has a Masters in Writing.

http://rebeccamascull.tumblr.com/

https://twitter.com/rebeccamascull

https://www.facebook.com/RebeccaMascull

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

The research sounds fascinating for this book and I now have it on my reading list. Definitely up my street, thanks for the insight! Popping over from #MondayBlogs

Thanks so much, Carol. The research was utterly fascinating. I learnt so much!

I suspect that we are only beginning to understand evolution and am fascinated by the topic. I have added Song of the Sea Maid and the other books mentioned in this post and comments to my TBR list.

Hello Natalia – I agree! It’s such a fascinating topic. I love the whole aquatic ape idea too…I do hope you enjoy the book. 🙂

I find the premise of your book fascinating and it reminds me of a book, actually several, by Elaine Morgan. The most easily accessible of these is The Descent of Woman, which proposes an alternative theory of evolution, predicated on the idea that women’s needs to protect their offspring let to a period of semi-aquatic life in our development. You may find her writing interesting as will-if you’re not already familiar with it!

Thanks so much, Wendy. I’m so pleased you mentioned Elaine Morgan, as I’m a big fan! If you see my Author’s Note at the end of the novel, I do mention The Descent of Woman! So you’re spot on there. Wonderful books aren’t they! Such a fascinating alternative theory.