On Finding The Right Writing Advice

In his poem ‘In My Craft or Sullen Art’, Dylan Thomas tells of his writing being ‘Exercised in the still night / When only the moon rages / And the lovers lie abed.’ It’s a seemingly perfect image – a writer, scribbling away at a desk set before a window, his ink drying under a white spill of moonlight.

In his poem ‘In My Craft or Sullen Art’, Dylan Thomas tells of his writing being ‘Exercised in the still night / When only the moon rages / And the lovers lie abed.’ It’s a seemingly perfect image – a writer, scribbling away at a desk set before a window, his ink drying under a white spill of moonlight.

Thomas’ words struck me. ‘These spindrift pages’ of his were, I imagined, just like mine. We had shared in this act of ‘labour’. There is a certain magic to writing – reflected, I think, in this short poem. Writers often attempt to describe that moment, when the words flow, and the characters speak for themselves, and the imagery sparks, and it all just fits.

But those moments are rare. And I am not keen to dwell on them here. What I am more interested in discussing is what comes before, between, and after those moments. The ‘labour’. The graft. Because writing, like any other skill, requires simple graft above all else. The hard work is what leads to the magic.

How then does the writer go about beginning to write, or improving their craft? How do they find the will to just keep going?

The simple answer is by putting words on the page.

There are a thousand snippets of advice out there… Some writers insist on a routine (begin work at 5am, write for three hours, breakfast, and so on).

Some set a daily wordcount and meet it, come what may. Some recommend downing tools and going for a walk when the flow abandons them. There are, of course, a thousand snippets of advice to choose from because every writer is different.

Finding the ‘right way’ depends upon trial and error. I always wanted to be a writer with a routine: wake before dawn, run, eat a fruit and yoghurt breakfast, arrive at my desk feeling energetic and patter out an entire chapter on an old typewriter with those wonderful, noisy keys.

Where am I writing this? On my settee, on a cheap laptop, pinned down by three sleeping dogs. And that’s fine, if it works. Because I don’t run, and I crave warm food at breakfast, and those ideas I once had don’t put words on the page.

I have learnt to give up on my perceptions about writing and grasp my opportunities instead. Ideally, I would write at a good desk set before a window or outdoors (and sometimes I do). Other times, I write in car parks, in waiting rooms, while I walk my dogs. Walking is part of that magic: it seems that there is some connect between stomping over sandy beaches or through woodlands and the mind’s ability to work through the words, the plot points, the character arcs.

Perhaps it is something to do with rhythm, I don’t know. But what I do know is that it works, for me. So I’ll stick with it.

Virginia Woolf wrote, ‘When I cannot see words curling like rings of smoke round me I am in darkness—I am nothing.’ I can sympathise with this sentiment. I don’t know how not to write. Even if I am not physically writing or typing, I am usually thinking about words. The entire process occupies my thoughts in a way I have no real control of.

What I do have control of, however, is improving my practice.

I have claimed that we must all find our own way as writers, and so we must, but if you’ll permit me, I’d like to share what helps me.

Louisa May Alcott wrote, ‘I like good strong words that mean something…’

It sounds so obvious, so necessary, and yet, it required a lot of practice for me to stop hedging my bets. I used to make liberal use of the word ‘almost’. It was ‘almost black’, ‘almost winter’. I have since persuaded myself into the confidence to say exactly what I mean – or as close as I can get.

In my experience, nothing ever reaches the page in the same perfect state as I first encounter it in my imagination. It is lessened, by the act of translating the idea into language, but what joy there is in the effort. There is nothing I love more than playing with words: rearranging them, tightening them, discovering them. Trying to shape them into something which reflects my story, my characters. And different stories call for different approaches.

Joan Aiken wrote, ‘Words are like spices. Too many is worse than too few.’

And true, there are writers out there who would claim the adverb as the devil himself – never, under any circumstances, to be allowed access to the story. I would disagree. As I’ve said, I think it unwise to claim one way. But I do think it’s worthwhile to keep Aiken’s advice in mind: why use two words if one will say it? Why opt for ‘he ran desperately’ if ‘he galloped’ will do the job?

Stephen King claims that, ‘Any word you have to hunt for in a thesaurus is the wrong word. There are no exceptions to this rule.’

Again, naturally, there are exceptions to this rule. There are exceptions to every rule. But it’s most certainly worth asking yourself, when you read back over your work, whether you can hear the author in the writing. The author doesn’t belong there, visible for all to see. They belong behind the words, hidden almost entirely (the ‘almost’ here is intentional; there really is an exception to every rule).

I could weave in and out of ideas about writing forever. I’m sure my own conclusions will continue to change as I continue to write. But if I had to restrict myself to a few snippets of my own, I suppose I would say…

- Never stop reading.

- Every writer needs fresh eyes; find readers who are willing to offer honest feedback.

- Read your work aloud; you will hear whether it is working or not.

- Pick and choose the advice which works best for you; you are absolutely entitled to disregard the tips of the masters if they do not serve your practice.

- But, accept that if you are continually receiving the same advice, other people might just be right, and learn from them.

- Enjoy the process (even the editing); you might well only get one chance to tell that particular story.

In his book of essays, Daemon Voices, Philip Pullman writes, ‘the reader wants to know what happened next. So tell them.’ That reminder makes me laugh every time I read it, and yet, I can’t think of better advice. It is all too easily forgotten. So…

7. Remember to ask yourself whether what you are writing serves to drive the story forward. If it doesn’t, you probably don’t need it.

We want to hear the rest of the story, so tell us.

—

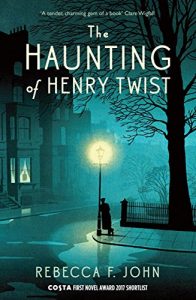

London, 1926: Henry Twist’s heavily pregnant wife leaves home to meet a friend. On the way, she is hit by a bus and killed, though miraculously the baby survives. Henry is left with nothing but his new daughter – a single father in a world without single fathers. He hurries the baby home, terrified that she’ll be taken from him. Racked with guilt and fear, he stays away from prying eyes, walking her through the streets at night, under cover of darkness.

London, 1926: Henry Twist’s heavily pregnant wife leaves home to meet a friend. On the way, she is hit by a bus and killed, though miraculously the baby survives. Henry is left with nothing but his new daughter – a single father in a world without single fathers. He hurries the baby home, terrified that she’ll be taken from him. Racked with guilt and fear, he stays away from prying eyes, walking her through the streets at night, under cover of darkness.

But one evening, a strange man steps out of the shadows and addresses Henry by name. The man says that he has lost his memory, but that his name is Jack. Henry is both afraid of and drawn to Jack, and the more time they spend together, the more Henry sees that this man has echoes of his dead wife. His mannerisms, some things he says … And so Henry wonders, has his wife returned to him? Has he conjured Jack himself from thin air? Or is he in the grip of a sophisticated con man? Who really sent him?

Set in a postwar London where the Bright Young Things dance into dawn at garden parties hosted by generous old Monty, The Haunting of Henry Twist is a novel about the limits and potential of love and of grief. It is about the lengths we will go to hold on to what is precious to us, what we will forgive of those we love, and what we will sacrifice for the sake of our own happiness.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips