The Default Male in Books – Megan Campisi

This is an article about two things: the “default male” in books and how I was once mounted by a cow. They are related, I promise.

This is an article about two things: the “default male” in books and how I was once mounted by a cow. They are related, I promise.

Why don’t we start with the juiciest? In the 2000s, I was a sort of assistant ranger at an educational farm in California. It wasn’t a bad job. I’m outdoorsy by nature and don’t mind physical labor. I even liked my uniform with its ranger patch and name tag. Oh, and I got to wear a big round hat.

A farm is a rather female place. Imagine a herd of bulls or a flock of roosters. Doesn’t happen. Females produce milk, meat, wool, and most importantly, offspring. You usually don’t need more than one male around. And male farm animals are often larger, belligerent, and, I’ll say, promiscuous. They’re bred for it. You don’t want your stock shy about mating or you’ve got zoo pandas.

What was interesting, however, is that when the public arrived at our educational farm, they would assume all the animals were male.

“Look at that donkey, he’s eating hay.”

“A chicken! Do you think he’ll lay an egg?”

And it wasn’t just the animals. My women-identifying colleagues and I were misgendered regularly, too. People would see the uniform, the hat, the heavy labor, and it would be: “Excuse me, sir, where is the herd of billy goats?” Male was just the default gender.

It intrigued me. I pondered it while doing things like shoveling manure and feeding sheep. And being mounted by a cow. Yes, we’re finally getting to it.

Clover was an 18-month-old heifer. She weighed in at about eight hundred pounds. She was the more assertive of the two heifers on our farm.

Clover would barrel into you as you pushed the feed wheelbarrow, spilling its contents into the dirt to get a fifteen-second jump on mealtime. And don’t forget, if males are bred for size and promiscuity, that means females are too. Clover went into heat on a monthly basis and would get into some frisky bucking and frenzied sprints accompanying her ovulation. Maybe you see where this is going.

The farm was quiet on the morning of the incident. A parent had asked me (“Pardon me, sir?”) if I could take her six-year-old along while I fed the sheep. The child and I had just crossed the cow corral to the sheep paddock, when I paused to unlatch the gate. Which is when a hoof slid over my right shoulder. Then another hoof slid over my left shoulder. This was no twenty-pound puppy humping my leg; this was a nearly half-ton heifer leaning on my shoulders looking for love.

Time moves really slowly in near-death farm experiences. I’m proud to say my first thoughts were for the child. I placed my hands atop the fence to brace against Clover’s weight, forming a protective shell around the kid. While the hooves shifted on my shoulders, I asked myself: What does imminent paralysis feel like?

And: Can anyone’s memory transcend death-by-horny-heifer?

Meanwhile, the kid couldn’t really see what was going and was starting to ask questions like: “Are we going to feed the sheep soon?” and “Is that my mom yelling?”

Suddenly, with a jerk and a start, the hooves slid from my shoulders. I stood frozen. You’re not supposed to move someone with a spinal injury. But female cattle aren’t “supposed” to mount people either, so I was already off script. I lifted the six-year-old over the fence into the next paddock. The kid happily gamboled past two placid donkeys to meet a rather agitated mom.

Soon after, I also met the mom. She voiced some very legitimate concerns about the safety of her child. My thoughts moved from imminent paralysis to imminent litigation. She wanted answers: “Why did that bull do that?” Honestly, I couldn’t say.

Because the child was fine, the mom finally got around to asking if I was okay. And, surprisingly, I was. Really, my dignity was the only thing bruised, and that was soothed with a burger for dinner.

Still, the mother’s question lingered, why did that “bull” mount me? Females aren’t supposed to be physically aggressive and express intense sexual desire, right? But, of course, that’s not true. Female animals run a wide gambit of aggressivity and promiscuity, all of it “supposed” to be there. Sometimes we forget about female great white sharks, female rabbits, female pit vipers. I wondered, what was it in our experience that sets these gender defaults in place?

Fast-forward twenty years. I have kids of my own, and I’m super excited to share the books from my childhood with them. This is where my imagination first dug in and took root, with Wild Things and Cats in Hats and Hungry Caterpillars. But when I started re-reading these books, I noticed there were stories about boys and stories about girls.

Max is a boy who visits the Wild Things. Madeline is a girl living in Paris. Fine. Good. But the caterpillar? He’s a he too. And the Cat in the Hat? Also male. Big Bad Wolves? Boys. The ogre under the bridge? He/him. English has a gender-neutral pronoun.

These characters could be it. The caterpillar, it eats two pears. But that’s not what happens. He eats the pears. When gender doesn’t matter, gender is male. (And race? There’s a default white male too, like the one who flashes at the crosswalk to tell us when we can go.) The gender default isn’t just on the farm, it’s in our books. The very first ones we introduce to our kids.

I tried an experiment. I reversed the gender of the characters in the books. Instead of he for the caterpillar and the Cat, I tried using she.

“Mom,” my kids—3 and 5 at the time—interrupted. “Those aren’t girls.”

“How do you know?” I asked.

“Girls have bows in their hair.”

I kept switching up the default male genders—swimming fish, cookie-eating monsters—I’d call them it one time, he the next, then she. Gradually, my kids became accustomed to it. Maybe I just wore them down. But they started to ask my questions back to me.

“How do you know if the monster’s a he or a she?” asked my younger kid.

“What if they’re a they?” asked my older.

I asked back, “Does it matter?”

They weren’t sure. I’m not either. But I wonder if we never learn to imagine female wild things and she-wolves, does it make it harder to recognize women farmers? If there’s no space for a non-binary monster, does it make it more difficult to imagine all genders of surgeons and firefighters and pilots and presidents?

Does only ever knowing women as the cute and docile characters mean that somewhere in our deepest imagination women always have bows in our hair? What if part of growing up and surviving in this world is having a little Big, Bad in you? Being able to blow the house down? Or hold your own against an ovulating heifer, however you identify? What if I want to raise kids who recognize first and foremost, not one gender or another, but human? Can it start with the books we read?

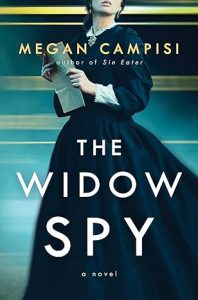

My new novel, The Widow Spy, is about the real-life first woman detective, Kate Warne. She foiled train robbers, caught murderers, and was a spy for the Union during the Civil War. According to historical record, Warne walked into Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency one day and asked for a job.

Pinkerton assumed she wanted to be a secretary, but Kate convinced him she would be invaluable as a detective because she could “worm out secrets in many places to which it was impossible for male detectives to gain access.” She joined the agency in 1856, fifty years before the police force began hiring women detectives.

In my telling, Kate was inspired by the detective books she read as a child at the public library. Those books were about boys, and it took a great leap of imagination to envision herself in the role she eventually stepped into. In doing so, she helped change the gender expectations in detective work.

In writing stories about women in traditionally male roles—from detectives to wild things to farmers—authors make that leap of imagination a little easier to land. There’s a strong and growing body of stories leaving behind the default male. As a dear friend reminded me recently, progress is slow, but it’s worth celebrating the wins!

If Kate had been born later, she would have had Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh, Nancy Drew Mystery Stories by Carolyn Keene and The Enola Holmes Mysteries by Nancy Springer to take root in her imagination, changing assumptions and expectations.

Soon, maybe the binaries of yesteryear can stay in the past and we can move forward into a place where detectives and hairbows and heifers don’t have a default gender. Where we can be, first and foremost, human.

—

Find out more about Megan on her website https://www.megancampisi.com/

THE WIDOW SPY

The author of the “magnificent…complex, vivid” (New York Journal of Books) Sin Eater returns with a rousing and propulsive novel based on the astonishing true story of the first female Pinkerton detective whose next assignment could end the Civil War.

The author of the “magnificent…complex, vivid” (New York Journal of Books) Sin Eater returns with a rousing and propulsive novel based on the astonishing true story of the first female Pinkerton detective whose next assignment could end the Civil War.

Kate Warne is many things: the country’s first female detective, a Pinkerton agent, and a union spy.

It’s August 1861, and her latest assignment could finally end the bloody war and bring the fractured United States together again. All she has to do is win the trust of her captive: Confederate spy and socialite Rose Greenhow. But with Rose well aware of Kate’s working-class background and belief in abolitionism, it seems an impossible task. Worst, Kate has secrets that make her vulnerable, such as her forbidden love affair with a colleague.

With time running out, Kate faces not only the moral and political divides between herself and Rose but also the ones she made in her own heart and life. Can she make the difficult decision over which divides are worth crossing? Or will she fail the most important assignment of her career in this spellbinding and moving new novel from Megan Campisi?

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing