A Wrinkle in my Time-Line

“What are you reading?”

“What are you reading?”

My friend Tina was a bit of a bookworm; that was one reason why we were friends. But this was the first time she’d taken a book out to read every break time and lunch time, sloping off to the edges of the school field where footballs and nosey friends wouldn’t bother her.

She proffered a book, but I was none the wiser.

“A Wrinkle in Time?” I said. “What’s it about?”

“Sort of sci-fi. There’s three witches but they’re not really witches and a girl called Meg who goes to look for her missing dad and a giant brain called IT.”

I sniffed.

“It’s brilliant,” she said, fiercely, and turned away to continue reading.

There wasn’t that much in the school library or the town library that would have inspired the word brilliant or the fierce, excited tone of voice. If you grew up in the UK during a certain era, as I did, children’s fiction was largely dominated by old classics and Enid Blyton.

Books stayed on the library shelves forever and new ones were rare. I read Blyton because there wasn’t much choice, and I soon wearied of her stories, of George the tomboy, Anne the little home-maker who was always frightened, of the various strapping, jolly heroines of boarding school tales. In recent years I’ve seen some very disturbing explorations of just what was wrong with those books, but most of us do still look back on them with fondness of sorts.

The trouble was, there were so few really relatable female main characters, ones I could really feel were at all like me. So when Tina finished the book, it had barely a chance to land back in the library before I seized it and devoured it too.

Meg Murry was a revelation. A misfit, awkward, highly intelligent but too stubborn to play the games school requires, brave even though she was terrified, loving but not soppy, and utterly different from anyone I’d encountered in fiction before. The story, so powerfully and convincingly woven, touched on realities I had always felt were there but never could reach. I spent many hours giving myself a headache trying to “tesser” after that.

A few Christmases ago, my brother gave me a box-set of the entire series of the Time novels. I’d not realised until then that Madeleine L’Engle’s Time Quintet existed and I savoured each novel. Meg grew up into a woman I admired but the girl she was still holds a place in my heart because it was the first time a truly complex female character had confronted me with the possibilities of how you could write women in fiction. L’Engle’s faith also informed and infused her fiction without ever being preachy or twee, and that too appeals to me even more now.

A couple of years later, at high school, we were set A Wizard of Earthsea to read and to study. I devoured it but could not quite accept how lowly the roles of women were in that first tale. Consigned to the hearth like the sister of Ged’s friend, or dismissed with the adage Weak as Women’s magic or Wicked as Women’s magic or as temptresses like the sorceress Ged had known as a boy, who grew into her power and beauty and snared a rich and evil husband, none of the women took centre stage.

A few years later I bought the Earthsea trilogy and in The Tombs of Atuan, I found the woman who later became the dominant force in the later novels: Tenar of the Ring. The young Tenar, robbed of her name and known only by her priestess name of Arha, rebels against her life of stifling routine and rituals but not by trivial restlessness but by (quite literally) undermining the entire cult she belongs to.

In the later books, Tehanu and The Other Wind, Tenar comes more and more into her own, becoming a woman that I can relate to in her strength, her pragmatism and the way she embraces the changes of life as she ages. Girl and woman, and even crone, she’s a role model like no other. Le Guin’s atheism, like L’Engle’s faith, informs her narratives and drives them along, and that too appeals to me, as my faith ebbs and flows and sometimes vanishes entirely.

In my own writing, begun around the same time I first read A Wrinkle in Time, I have always sought to create female characters who mirror something of the girl I once was, who admired Meg Murry and Tenar of the Ring, and aimed for them be more than the cardboard stereotypes that populated much of the literature of my youth.

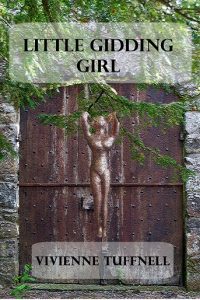

Yet with my latest book, the main character Verity reflects more the girl I was than do Isobel (from Away With The Fairies) or Chloe (from Square Peg). Hesitant, nervous, easily bullied, she’s not kick-ass/sassy/savvy or even independent.

In Little Gidding Girl I wanted to show how sometimes we get lost, turned around and confused by the hard knocks life gives us, and some of us never quite get over those knocks until something beyond ourselves intervenes. In Verity’s case, it’s more like the arrival of Mrs Whatsit in the kitchen one dark and stormy night, than the arrival of a questing wizard seeking to find a lost treasure in an ancient labyrinth guarded by timeless and dark spirits. Her journey, like that of Meg’s, involves a form of time travel, and like Meg, she does not return to ordinary life unchanged by he

In Little Gidding Girl I wanted to show how sometimes we get lost, turned around and confused by the hard knocks life gives us, and some of us never quite get over those knocks until something beyond ourselves intervenes. In Verity’s case, it’s more like the arrival of Mrs Whatsit in the kitchen one dark and stormy night, than the arrival of a questing wizard seeking to find a lost treasure in an ancient labyrinth guarded by timeless and dark spirits. Her journey, like that of Meg’s, involves a form of time travel, and like Meg, she does not return to ordinary life unchanged by he

—

Vivienne Tuffnell is a writer who seeks to explore the hidden side of human existence, delving into both mysticism, the paranormal and deep psychology in her stories. She writes character-driven fiction, soul-filled poetry and blogs about soul growth at http://zenandtheartoftightropewalking.wordpress.com.

She has self-published six novels, two collections of short stories, a novella, several collections of poetry, a book of essays on mental health and a book of guided meditations using scent.

Vivienne lives at present in Norfolk, England with her husband, her daughter, two cats and a small herd of guinea pigs, and works part-time as a tour guide and courier for a travel company.

Her latest novel Little Gidding Girl was published at midsummer and explores youthful dreams and their loss, love, and the nature of time itself. It is available in paperback and e-book format from all Amazon stores.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing