I Now Call Myself A BAME Writer

I never used to call myself a writer – let alone a black, Asian or minority ethnic one. I kept my writing private, confining it to a world that consisted only of my laptop, the occasional scrap of paper, and me.

I never used to call myself a writer – let alone a black, Asian or minority ethnic one. I kept my writing private, confining it to a world that consisted only of my laptop, the occasional scrap of paper, and me.

When I started my first novel I knew things would have to change, and that if I really was going to ‘make it’, I would have to open up. Still, I kept my writing world offline as long as I could, and I steered clear of Twitter and writing forums. When I started my masters in creative writing that world expanded just a bit to include my tutors and classmates. And while I welcomed as much feedback and work-shopping as I could get, I still found it difficult to discuss my work aloud.

See, although I’d moved to London with dreams of being a published author, I didn’t necessarily want to be part of the writing and publishing world. In my head, my job was to the write book, and that abstract thing that was the publishing industry – with some hard work and good luck – would do the rest.

That’s probably why I was so naïve about how the industry worked, and the chances of a BAME a writer having her work picked up a traditional publishing house. I had no idea that the vast majority of agents, editors and publishers in the UK are white, and of the thousands and thousands of books published each year, as reported by The Bookseller last November, fewer than one hundred are written by someone of a BAME background.

Despite being an avid reader my whole life, somehow I’d failed to pick up this glaring lack of representation. I’d never processed the fact that the type of book I wanted to write – a romantic comedy featuring a non-white heroine – was few and far between. That so rarely I have come across books about characters who looked like me, or had families like mine. Characters that had diverse backgrounds and experiences. Characters in which I could clearly see myself.

The truth is, I’d subconsciously accepted the fact that someone like me doesn’t often get to be the heroine in books, film and other media – and I simply didn’t have any expectations that things could be different.

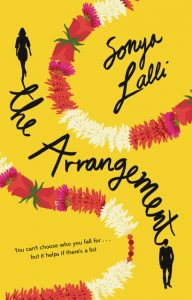

When I finished a draft of The Arrangement two years ago, I forced myself to look up. Slowly but surely, I realized how real of an issue diversity in publishing truly is. It was disheartening to say the least, but eventually I did find a wonderful agent and publishing house that were interested in the story I had to tell. And they loved my work irrespective of the fact that my story was a bit different than what readers were used to, and wasn’t necessarily an easy sale. They made it better and real and championed it, and as of 10 August, it will be out in the world.

My journey as an aspiring to published author has come at a transformative time in the publishing industry. In recent years there seems to have been a general acknowledgement that the lack of diversity is a systemic issue, and most of the big five publishers have developed programmes to foster diversity among staff and authors. More (but still not all) publishers are realizing that unpaid internships act as a class and race barrier, and BAME industry folk are able to connect through fantastic initiatives like the BAME in Publishing network launched by Sarah Shaffi and Wei Ming Kam.

In the past year, we’ve also seen The Good Immigrant, edited by activist and writer Nikesh Shukla, voted in as the UK’s best book in 2016, and other diverse anthologies come to the fore – such as A Change is Gonna Come (featuring BAME voices in YA) and The Things I Would Tell You: British Muslim Women Write, edited by Sabrina Mahfouz. Shukla and Sunny Sing have also launched the Jhalak Prize, an award that recognises outstanding writers of colour.

All of this is a step in the right direction, but it’s still early days – and the industry has its work cut out for it. Those with power in the boardroom have yet to prove that their so-called commitment to diversity will indeed create real change, and the groundswell of BAME writers, publishers and their allies must stay in lockstep to enforce that change.

While a part of me wants to turn off my Wi-Fi and unplug from the world while I sit down to write my next novel, a larger part of me is ready to have a voice. One that says I’m proud of my background, experiences and stories – and I will do whatever I can to help make sure every other writer of colour feels the same way.

—

Would you let your grandmother play matchmaker?

Would you let your grandmother play matchmaker?

You can’t choose who you fall for…but it helps if there’s a list

When you’re approaching thirty it’s normal (if not incredibly annoying) for your family to ask when you’ll tie the knot and settle down. But for Raina there’s a whole community waiting for someone to make her a wife – and a loving grandmother, Nani, ready to play matchmaker with a comprehensive list of potential husbands.

Eager not to disappoint her family, Raina goes along with the plan but when the love of her life returns – ex-boyfriend Dev – she’s forced to confront her true feelings. Now her ‘clock is ticking’, it’s time for Raina to decide what she actually wants.

Will Raina let her family decide her future, or can she forge her own path?

Praise for THE ARRANGEMENT – a heartwarming and uplifting romantic comedy:

‘A riotous odyssey into the pressures of cross-cultural modern dating’ ELLE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips, On Writing