Walking my Way to Writing

I have scribbled and strode my way through more than half a century of life, from the various neglects and insults of my childhood, through the frustrations and intimacies of relationships, marriages, and separations, to the frantic helplessness of health setbacks, the hard-won lessons gifted to me by my dogs, the slack-jawed joys of watching nature do her thing, the unexpected kindnesses of friends, and so much more.

I have scribbled and strode my way through more than half a century of life, from the various neglects and insults of my childhood, through the frustrations and intimacies of relationships, marriages, and separations, to the frantic helplessness of health setbacks, the hard-won lessons gifted to me by my dogs, the slack-jawed joys of watching nature do her thing, the unexpected kindnesses of friends, and so much more.

Through all the unexpected reversals of fortune and turns of events, from hopeful to defeated to joyous to melancholy and back again, the movement of my pen on paper and my feet on trails has both deepened my gratitude and given me back some of what years of living takes away. Perhaps the only occupations that have absorbed more of my hours on earth are those essential to staying alive, such as eating and sleeping. Perhaps, when it comes right down to it, walking and writing are just as essential, at least to my life.

Of course, many people jot in their journals and take a stroll before dinner, hike with one friend and write letters back and forth with another. But for a certain subset of people, for those who take writing seriously enough to engage in the sustained effort of crafting something – a poem, essay, story, novel – with the intention that it might someday be read by untold numbers of strangers, walking and writing are often, rather famously, entwined. Many writers have tried to capture the nature of this generative symbiosis. “Me thinks that the moment my legs begin to move,” wrote Henry David Thoreau, “my thoughts begin to flow.” “He is the richest man who pays the largest debt to his shoemaker,” said Ralph Waldo Emerson.

More recently, even science has weighed in. Studies confirm what we viscerally know. Walking, like any exercise, increases blood flow, which improves physical and mental fitness by building stamina and strength and encouraging brain cells to make new connections, grow new neurons, and speed messaging. While any exercise is good for the body and brain, walking seems uniquely suited to enhancing thinking. Tests have shown that putting one foot in front of the other fosters creative thinking and results in more nuanced and novel problem solving. This effect holds true whether the forward motion occurs on a treadmill staring at a blank wall, surrounded by trees on woodland trails, or hemmed in by buildings and traffic on urban sidewalks.

Similarly, the heavy lifting demanded by writing is well documented. As Thomas Edison said, “Genius is 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration.” For me, when I’m at my desk, writing is all sweaty grunt work. I mean this in the best possible way. It is engaging and completely consuming, each word and phrase a stone that needs to be lifted, assessed, likely set aside as not quite right while another is picked up, nudged, shimmed, and thereby carefully fitted into place, one by one, each rock coming together to create the hand-built edifice that may become a book.

Then, when my body is numbed and my thoughts sludged with all that toil, I stand upright, my knees cracking, my knuckles aching, and I go somewhere, preferably with only the dog for company. I let my legs take me away, literally and metaphorically. As I walk, I don’t think of the effort in front of me or of that I left behind. I don’t try to achieve any particular state of mind. I simply put one foot in front of another, and notice what nature chooses to show me.

As things appear in front of my eyes – a brief disturbance in the undergrowth, a stream diminished by a warmer season, a raven dropping from a branch, wings snapping like sheets in the wind – things also make themselves known inside my head. A well-formed phrase presents itself like a bright leaf tacking back and forth on the still air beneath the high canopy, winking at me in the shadows; a new plot point wrests itself from a sticking point like a delicate butterfly lifting from a small patch of mud on an otherwise dry day; a new character swoops down on me, a sudden, silent movement, like an owl cutting across the trail before it plops onto a branch and regards me from on high with its twisting head and inscrutable eyes.

Sometimes, I take notes of what has come, seemingly unbidden, into my mental path, capturing the gift as if it were an oddly shaped stone or a compelling piece of sea glass. Sometimes, I let the thoughts continue on their own journey, confident their essence and wisdom will still be with me when I return to the labors of my desk. And here is perhaps the essential truth of why walking, a totally natural, innate, automatic activity, confers such salutary effects to both our brains and our minds: walking wakes our bodies, while setting our thoughts free.

People often ask me, where do you get your ideas? It seems to me that ideas are easy to find. Every daily experience, exchange, and relationship is brimming with the possibility of a story. I think the more challenging question is, what do you do with your ideas? Certainly, I write them down. But perhaps more important, I walk them down.

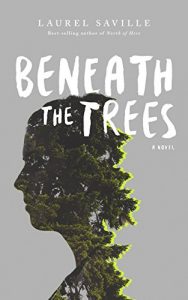

About Laurel Saville

Laurel Saville is an award-winning author of numerous books, articles, essays, and short fiction. Her work has appeared in the LA Times Magazine, The Bark, NYTimes.com, Good Housekeeping, The Bennington Review, Elle.com, House Beautiful, Room, Seven Days, and other publications. Her books include Beneath the Trees, North of Here, Henry and Rachel and Unraveling Anne. She holds an MFA from The Bennington Writer’s Seminars and lives and writes near Seattle.

About Beneath the Trees

An ambitious wildlife biologist, Colden McComb hikes the rugged Adirondack mountains, tracking moose and beaver, and navigates the halls of academia, jockeying for a place in the male-dominated world of conservation research. Over the course of one tumultuous year, she becomes entangled with a series of unsettling events that none of her scientific training can help her explain.

An ambitious wildlife biologist, Colden McComb hikes the rugged Adirondack mountains, tracking moose and beaver, and navigates the halls of academia, jockeying for a place in the male-dominated world of conservation research. Over the course of one tumultuous year, she becomes entangled with a series of unsettling events that none of her scientific training can help her explain.

Best-selling author Laurel Saville uses incisive prose and evocative imagery in another page-turning story that picks up where her novel, “North of Here,” ended. She brings readers into the brooding backcounty of Upstate New York, where Colden searches for connections between petty thefts, sabotage vandalism, sexually-explicit emails, office gossip, Sasquatch myths, grainy game-camera images, an elusive chimera, a teenage runaway, and the contradictions of her own heritage. Alongside her handyman father, social worker step-mother, and a lawyer with secrets of his own, Colden confronts the mysteries she finds beneath the trees, and also within her own heart.

Category: On Writing