HOW TO WRITE FICTION ABOUT THE UGLY PARTS OF OUR PAST

The first time I met him, my father-in-law Art regaled me with stories of the Spanish conquistador who claimed territory and opened trade routes for his queen before he traveled to California, married a local woman and sired Art’s family tree. His connection to this valiant man was a great source of pride, but what he didn’t know was that the story wasn’t true.

The first time I met him, my father-in-law Art regaled me with stories of the Spanish conquistador who claimed territory and opened trade routes for his queen before he traveled to California, married a local woman and sired Art’s family tree. His connection to this valiant man was a great source of pride, but what he didn’t know was that the story wasn’t true.

I used a genealogy site to uncover all I could about Art’s conquistador connection. I hoped to be able to find documentation of his ancestor’s swashbuckling and present the information to him on his 85th birthday. Unfortunately, I learned the so-called conquistador was, in fact, “Mexican Prisoner Number Four” — a criminal who made his way to California to start a new life after his release.

I’m not sure whether the prisoner sold himself as the conquistador Art believed him to be, or other family members changed the story later to avoid embarrassment. However the lie came about, my father-in-law and his family aren’t unique. Plenty of families hide skeletons behind more appealing, albeit fictitious, versions of their history. It’s not easy to accept the ugly parts of the past, whether it’s our family’s past, our community’s or our country’s.

This is nothing new. In fact Americans’ tendency to airbrush the past is so widely recognized books have been written about it, like 1995’s “Lies My Teacher Told Me,” by James Loewen. Loewen posited that history textbooks got America’s story wrong by avoiding controversy, oversimplifying events and elevating complex historical figures (think Thomas Jefferson, who failed to free his own slaves) to hero status. Popular author Malcolm Gladwell has found more than enough material for his new podcast, “Revisionist History,” which reinterprets well-known past events, from a U.S. intelligence operation in 1965 Saigon to 2009’s massive Toyota recall for unexpected acceleration. “Because sometimes,” Gladwell writes on Twitter, “the past deserves a second chance.”

As a former journalist, I reported on some fairly controversial events from America’s recent past. I covered the 25th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court decision that protects a woman’s right to choose whether or not to terminate her pregnancy; and later, another anniversary, this time of the infamous 1998 murder of Robert Byrd, a black man who was killed in Texas when two white supremacists chained him to the back of a pickup truck and dragged him for three miles. Covering those events wasn’t easy, but I knew that, to paraphrase the Society of Professional Journalists’ (SPJ) ethics code, my job was to report everything I knew fairly and accurately.

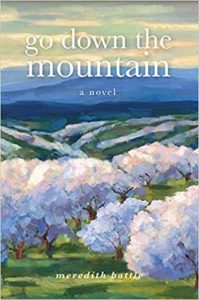

When I set out to write, “Go Down the Mountain,” a historical fiction novel set in 1930s Appalachia during the eugenics movement, the objectives weren’t so clearly defined. How do you write about controversial historical events when you’re not just presenting information, you’re fictionalizing it? And what do you say to the descendants of the people you’re writing about if they don’t like what you’ve written?

I exchanged nonfiction writing for fiction a long time ago, but I knew that, out of respect for the people I was writing about, I wanted the novel to be more than one salacious anecdote after another. I wanted it to be largely fact based, so I started what would become months of research.

I knew eugenicists sought to preserve the “purity of the American race” through the forcible sterilization of people deemed inferior: poor people, immigrants and people of color — the majority of whom were women. Through research I learned that, while there was no mention of the American eugenics movement in my high school history textbooks, it was so extensive in this country that even Adolf Hitler took note. He mentioned it in “Mein Kampf” and enacted nearly identical sterilization laws when he assumed power in Germany in 1933. I also learned that a small number of the Appalachian people I was writing about were imprisoned and sterilized at the Virginia Colony for the Epileptic and Feebleminded.

I read books and articles by historians, sociologists and anthropologists, including the infamous 1933 book “Hollow Folk,” which mischaracterized Virginia’s mountain families as ignorant hillbillies and was used as justification for taking their land and committing some of them to the Virginia Colony. I listened to recorded interviews with people who had lived in the mountains, maintained by Virginia’s James Madison University. And I watched a documentary interview with a mountain woman who had been sterilized.

The more I learned the more important it became to share the story of what happened to these mountain people compassionately, but also accurately. I thought of my Dad’s family, from southern Appalachia, and how they would want to be portrayed. I knew there were things in my story that my grandparents, who passed away some time ago, would have wanted me to keep secret — their own version of my father-in-law’s “Mexican Prisoner Number Four.” My grandmother would have been embarrassed by talk of eugenics and the declaration that some Appalachians were inferior and shouldn’t be allowed to reproduce. But I also knew I had to include those parts of the story, because so many Americans still didn’t know the worst of what had happened in the mountains.

I wondered if, like my grandmother and other families with secrets, the descendants of the Appalachians in my book would rather I not mention the worst. I got my answer this April when I released my novel. In a matter of weeks, my author page went from 67 Facebook followers to 4,500. Every descendant who has reached out has thanked me for sharing the story.

It hasn’t all been roses, though. I did hear from one man (not a descendant) who said he didn’t believe anyone had been imprisoned and sterilized, because he’d never heard any mention of the practice. Since I had approached my research journalistically and aimed to write fiction that accurately recounted the past, I was able to cite a number of sources that confirmed what I had represented in my book.

I never told Art the truth about the conquistador who didn’t exist. It would have only hurt him. But some stories have to be shared – to honor the people affected and to learn lessons from the past. I believe the aim should be to write historical fiction with compassion and accuracy, even though it is ultimately fiction. I’ll let others be the judge of whether I accomplished this, but I hope any author who sets out to fictionalize a dark part of history will at least try.

—

Meredith Battle lives with her husband, son, dog and ducks in a 200-year-old house in the Virginia Piedmont, a short drive from the Blue Ridge Mountains. She visits Shenandoah National Park, the setting for her novel “Go Down the Mountain,” as often as she can. She is currently working on her second novel.

Follow her on Twitter https://twitter.com/MeredithLBattle

and Facebook https://www.facebook.com/AuthorMeredithBattle/

Their government painted them as ignorant hillbillies, then took their land. Now read the story of these Virginia mountain families, for the first time as historical fiction.

Their government painted them as ignorant hillbillies, then took their land. Now read the story of these Virginia mountain families, for the first time as historical fiction.Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post