Writing As A Field Biologist

Biological field work and writing are two professions at odds with one another. The former has long, hard hours of physical labor and does not generally pay well enough to offer time and space for the latter. For the good part of a decade I tried to make it work with my two loves. I scribbled down thoughts about scenes or characters on extra data sheets, in journals crouched in the back of my pickup, or sitting high on a boulder after a day backpacking into a remote field site. I wrote down revelations by the light of headlamp or campfire. I plopped down exhausted in front of a notebook after a day collecting data on breeding birds, walking the sandy washes of the desert southwest for miles on end in the hundred degree heat.

Biological field work and writing are two professions at odds with one another. The former has long, hard hours of physical labor and does not generally pay well enough to offer time and space for the latter. For the good part of a decade I tried to make it work with my two loves. I scribbled down thoughts about scenes or characters on extra data sheets, in journals crouched in the back of my pickup, or sitting high on a boulder after a day backpacking into a remote field site. I wrote down revelations by the light of headlamp or campfire. I plopped down exhausted in front of a notebook after a day collecting data on breeding birds, walking the sandy washes of the desert southwest for miles on end in the hundred degree heat.

And at the end of those exhausting days I squeezed out what little energy was left like the proverbial blood from a stone. And some days I simply had nothing left and the page remained blank. But when I could, I cradled the words and tried to gently mold them to best represent the vision and emotion of what I had just lived out in the field. On those days, the distinct language of wild spaces was fresh in my mind as I transcribed it onto the page.

Most of my work kept me in the West. Both in Mexico and the United States, often in the borderlands between. I remember the menacing feeling walking along a new border wall and feeling the metal drum on my fingertips. I thought a lot about how wildlife suffers for human folley. I wanted to tear it all down. Parts of the novel required historical research so whenever I had days or weeks off in either San Fracisco or Portland I would visit the Historical Societies there and photocopy like a madwoman.

All these bits and pieces of information got stuffed into three large canvas tote bags and became like my burden to bear, moving from state to state with me and my husband, my then boyfriend, as we trucked ourselves off to the next seasonal field job. We did alpine surveys, desert surveys, mountain surveys, grassland surveys, old growth surveys, xeric woodland surveys and more. All these different ecosystems branded themselves on my heart. I tried to steal pieces of each place to keep with me like a crow collecting shiny things.

But it wasn’t until I became pregnant with our first son that I was able to focus and shape all those notebooks, loose papers and photocopies into the form of a novel. It’s counterintuitive that a new mom would finally find the energy and time to write a novel, but it’s true. The process was slow, as is the case for most everything in those hazy, molasses-paced days of being a new parent. The soft quiet moments unique to new motherhood allowed me to finally collect all my experiences and research into one nest. Very slowly I wove them together as I had always intended to do, but hadn’t been able to sit still in one place long enough to do so. I filled my messy new nest with all the shiny trinkets and mementos from my years in the field.

Then, suddenly, out of necessity, I was back in the field working 12 hour days with an eight month old. My husband was also working those 12 hour days. The consulting job was hard but paid well. I almost completely broke down after a day of pumping breastmilk in the field and walking for miles with the bottles of liquid gold in my hip cooler, post-holing through the desert in 110 degree heat. I got into a regrettable fight with coworkers who wanted me to work more hours even after I insisted I had to get back to my infant son.

Reeling from crumbling friendships I picked my infant up from the rural makeshift daycare where someone was feeding him chocolate pudding and felt awash with grief, guilt and shame at having left him alone in the first place. But then, because I had to, the next day I dropped him back off at 5:00am and headed back out to the field.

And so cemented the theme of mothers overcoming hardship in my novel. In life I had often found myself in positions that were not easy, that required me to be strong and overcome adversity. But as a mother the stakes had just been raised. I had to find a way to balance motherhood, field work, and writing. And I just couldn’t do it.

Many writers have to make these tough choices between what fulfills them and what ultimately works for both them and their family. I returned to teaching writing at the community college and put aside my love for the field in order to nurture the love for my children and my writing. I miss the work still, but get out into the woods near my house almost every day. I binge bird when the spring and fall migrants come through the area. When May rolls around I perform breeding bird surveys for the city as a volunteer. With a group of other moms at my son’s elementary I help track the development of a pair of breeding Great Horned Owls in the woods by the school.

Keeping that specific language sharp that I had just begun to learn working in wild spaces is difficult. I take it as a good sign that my second son, at one and a half, prefers to call animals and things by the noise they make rather than their english names. He is wide open in his channeling of the language of his natural surroundings. I try to be a little like him, to listen the best I can to what the natural world has to say. When we go for walks together I like to pick up keepsakes and put them in my pocket to examine later. I turn the object over in my beak and brain, all while enjoying the comforts of home—a cup of coffee, a cookie baked in my own oven, the light from my office lamp, a cushioned chair in front of my computer. I appreciate these comforts as I push my mind back into the wilderness of memory to speak tentatively my second language, the language of trees and rocks and wild space.

—

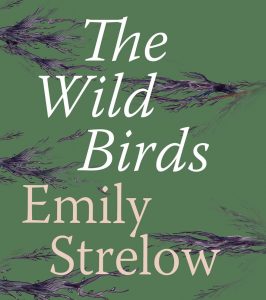

Emily Strelow has an MFA in Creative Writing from University of Washington in Seattle and an undergraduate degree in Environmental Science. She was twice a Glimmer Train Short Story Award for New Writers finalist. Her first novel, The Wild Birds, will be published March of 2018 with Rare Bird Books. She was born and raised in Oregon’s Willamette Valley but has lived all over the West. For the last decade she combined teaching writing with doing seasonal avian field biology. While doing field jobs she camped and wrote in remote areas in the desert, mountains and by the ocean. She is a mother to two boys, a naturalist, and a writer.

https://www.instagram.com/emilystrelow/

https://twitter.com/EmilyAStrelow

https://www.facebook.com/emilystrelowauthor/

About THE WILD BIRDS

Cast adrift in 1870s San Francisco after the death of her mother, a girl named Olive disguises herself as a boy and works as a lighthouse keeper’s assistant on the Farallon Islands to escape the dangers of a world unkind to young women. In 1941, nomad Victor scours the Sierras searching for refuge from a home to which he never belonged. And in the present day, precocious fifteen year-old Lily struggles, despite her willfulness, to find a place for herself amongst the small town attitudes of Burning Hills, Oregon.

Cast adrift in 1870s San Francisco after the death of her mother, a girl named Olive disguises herself as a boy and works as a lighthouse keeper’s assistant on the Farallon Islands to escape the dangers of a world unkind to young women. In 1941, nomad Victor scours the Sierras searching for refuge from a home to which he never belonged. And in the present day, precocious fifteen year-old Lily struggles, despite her willfulness, to find a place for herself amongst the small town attitudes of Burning Hills, Oregon.

Living alone with her hardscrabble mother Alice compounds the problem—though their unique relationship to the natural world ties them together, Alice keeps an awful secret from her daughter, one that threatens to ignite the tension growing between them.

Emily Strelow’s mesmerizing debut stitches together a sprawling saga of the feral Northwest across farmlands and deserts and generations: an American mosaic alive with birdsong and gunsmoke, held together by a silver box of eggshells—a long-ago gift from a mother to her daughter. Written with grace, grit, and an acute knowledge of how the past insists upon itself, The Wild Birds is a radiant and human story about the shelters we find and make along our crooked paths home.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips